The human body can only assimilate – i.e., absorb, without putting itself in danger – limited quantities of iron, sugar, iodine, carbon, etc. Our habitat, earth and its atmosphere, obeys the same laws. Too much sugar causes diabetes in the human body; too much greenhouse gas in the atmosphere induces a fever called global warming. Sustainable development for the earth is the equivalent of health in the human body – it does not demand that the earth absorb more than it can assimilate. The pursuit of this equilibrium implies that we must limit our desires and orientthem toward products and goods that are least costly in terms of substances extracted from the earth and the sea.

Photo: Michel Leblond- Le monde en images |

Of all of the activities we undertake in response to some desire ours, we must first move to limit those which are least related to work and its demands - e.g., travelling and sport. This discussion will be confined to a reflection on sport, but we should not lose sight of the close connection between the two. It soon becomes clear that we will soon have discovered many changes in sport practices, and that these these changes may include more benefits than drawbacks. It is clear, for example, that we benefit in moving from snowmobiling to cross-country skiing, or from motor boats to windsurfing. We are convinced, and wish to demonstrate here, that the same is true of most transitions to sporting practices that are more respectful of natural equilibria.

An “Ecoscopy” of Sport

Several years ago, many people were surprised, even shocked, to learn that an indoor ski slope was being erected in Dubai. An area the size of two football fields, it has to be cooled by 40 degrees. Perhaps this seems an extravagant luxury. But what right do we have to reproach Dubai? There are already about 50 such indoor ski hills in the world; the two longest ones are in Europe. Surely we can assume that there will soon be hundreds in Asia. But would it be preferable that the residents of Dubai charter airplanes instead, at the rate of 1500 passengers (the capacity of an indoor ski centre) each day, to go skiing in Switzerland? It is a question that raises a host of others: How much does it cost to transport professional sports teams – baseball, football, hockey – whose members crisscross the skies of America, Europe, and soon the entire world? What about Olympic sport, with major meets held every two years and competitions in various sports held around the world – don’t they leave a deeper and wider ecological footprint all the time?

And it isn’t only athletes who make long trips to fight over a ball: spectators do the same to witness the event. One study, reported in the April 16, 2005 issue of New Scientist, tells us that 73,000 spectators who watched a football match in Cardiff, Wales, had travelled a total of 48 million kms., half of that distance in cars. It would take one 2,670-hectare forest a year to absorb the carbon gas emissions of those 42,000,000 kms. If all the spectators had used the bus or train, the size of the footprint would have been reduced by twenty-four percent.

The History of Sport

A brief review of the story of modern sport will help us understand why it has taken the costly form that it has, and why it has spread through the entire world. It was essentially born in England in the nineteenth century, and it quickly conquered the countries in which capitalism made the most progress: France, Germany, and the United States. That explains why certain historians, notably Marxist historians, saw in sport a by-product and instrument of capitalism. Significant capital is required to create big professional teams. Moreover, the respect for authority and discipline critical in team sports are qualities that capitalist enterprises appreciate. Everyone knows, nevertheless, that the same sports have conquered socialist countries where, by about 1970, they achieved a degree of excellence that became the envy of capitalist countries.

If we cannot attach sports to either a particular political regime or to a specific type of economy, to what can we attach it? To religion? It is indisputable that Protestants were over-represented among the first medal winners in the modern Olympic Games; however, it must also be noted that religious barriers did not stop modern sports from establishing themselves around the world. Born in England, soccer (called “football” just about everywhere except North America) has as many homes now as there are countries around the world.

The strongest hypothesis is the one that attaches modern sport to modern science. Thus, for example, we may explain the essential difference between the Olympic Games of antiquity and those of today; the absence of numbers and records in the first case, the obsession with and the cult of “the record” in the second. If measurement of performance had interested them, the Greeks could easily have invented tools, water clocks for example, which would have allowed them to do it with a high degree of precision. But only the qualitative aspect of athletic prowess interested them; otherwise, it was enough to know who won.

“The emergence of modern sport does not represent either he triumph of capitalism nor the rise of Protestantism, but rather the slow development of the imperialist, experimental, and mathematical Weltanschauung (worldview). The first pioneers of sports in England had less to do with the Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism than with the intellectual revolution symbolized by the names Isaac Newton and John Locke and institutionalized by the Royal Society for the Advancement of Science, founded at the time of the Restoration, in 1662. (1)

In support of this hypothesis, Allen Guttmann cites the Dutch writer, Hans Lenk: “Performance sports, i.e., sports in which performance extends beyond the here and now, thanks to the comparison of results, is intimately linked to the scientific and experimental attitudes of the modern Western world.” (2)

French author, Jacques Ullmann, who also quotes Guttmann, compares Greek sport and modern sport: “Greek gymnastics were inseparable from a conception of the body, itself conditioned by a metaphysic of limits and finitude, whereas modern sport is a tribute to the idea of progress, according to which there are no limits to improvement.”(3) To the ancient Greeks, the idea of limits had a connotation so positive that its opposite, “unlimited,” was a synonym for evil. To not impose limits on one’s desires was to sink into the excess, into hubris. It is this very hubris that now threatens nature, just as it threatens the bodies of athletes. Within the context of modern sport, glory does not come from beauty attained while respecting limits, but from limitations surpassed at the risk of generating ugliness.

The three passages just cited were written after 1970, but the thesis they elucidate was formulated long before, by German philosopher Ludwig Klages. In his history of the modern West, he had already delineated the close link between the rise of formalism in the sciences, business, management, and sports. What Guttman calls “quantification” Klages calls “formalism.” (4) Klages does not, however, confine himself to noticing traits common to sport and other activities characteristic of modernity. He suggests an explanation of the phenomenon that embodies a valuable lesson for all who think a reorientation of sport has become essential.

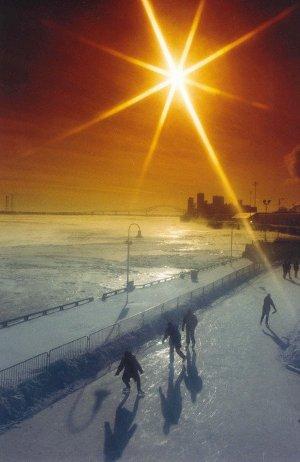

Photo: Hélène S. Dubois, Le monde en images. Patinage en Mauricie, au Québec. À l'horizon, le Pont de Trois-Rivières |

There are glorious winter days when it is impossible to resist the desire to skate or to ski, to abandon oneself to the pleasure of breathing pure air and to the joy of immersing oneself in the light and the beauty to the point where you become one with the landscape. No effort of will is necessary in that situation. That will is, on the contrary, necessary to keep you in front of the computer or television screen. But such is sport when it is still thought of as play, when it remains a spontaneous activity that is its own reward - free, illogical perhaps, free of every goal or end, including that of promoting health.

In Klages’ eyes, it is the soul, united to nature by a polar connection – the place of positive motives of admiration and of emotional approval – that expresses itself in this way. To this principle of life, he compares the spirit, giving to this word a very specific sense, close to the sense we give to the expression instrumental reason when we want to designate reason as a way of dominating the world rather than contemplating it. Just as many thinkers subscribe to the notion that modernity coincides with the rise of instrumental reason, Klages thinks that it is characterized by the rise of the spirit and is manifest in formalism. The link between the will and this spirit, in Klage’s perspective, is a strict one. In their relationship to their bodies and with nature, people today tend to substitute the will for the soul. This tendency, he clarifies, becomes manifest in the cult of the record, as it does in the excitement of the Stock Exchange where, in the spontaneous and free response of the soul to the call of life, the will is substituted for the soul, and the will seeks to attain a goal of numbers, a goal that can never be reached because the it keeps being increased, a goal that is clearly, purely arbitrary as compared to the fundamental needs of the human being. Sliding down this slope, people impoverish themselves, almost losing the capacity to see that their environment is becoming equally impoverished, sterile, eroded, purely functional. At a certain point, the will is nothing more than the will to power; it smothers the soul and reduces the body, heretofore a symbol of the soul, to an instrumentalized mechanism. The more that thought is at the service of the will, and the more the will frees itself, the more it identifies itself with an arbitrariness that is absolute.

Guttman leads us down the same trail as Klages. His book opens by recalling the poetic nature of the cosmic exhilaration a child experiences running on the beach at the edge of the sea. The child was Britain’s Roger Bannister. In 1954, he ran the mile in under four minutes – the first man to do so. Later in his book, Guttmann cites Bannister’s own testimony following this feat.

But let us listen first to the child: I remember a moment when I stood barefoot on firm dry sand by the beach. The air had a special quality as if it had a life of its own. The sound of breakers on the shore shut out all others. I looked up at the clouds, like great white-sailed galleons chasing proudly inland. I looked down at the regular ripples of the sand, and could not absorb such beauty.... In this supreme moment, I leapt in sheer joy. I was startled and frightened, by the tremendous excitement that so few steps could create. ... The earth seemed almost to move with me. I was running now and a fresh breeze entered my body. No longer conscious of my movement I discovered a new unity with nature. I had found a new source of power and beauty, a source I never dreamt existed.” (5)

And here is Bannister’s testimony after becoming a champion: “I had a moment of mixed joy and anguish, when my mind took over. It raced well ahead of my body and drew my body compelling forward. I felt that the moment of a lifetime had come. There was no pain, only a great unity of movement and aim. The world seemed to stand still, or it did not exist. The only reality was the next 200 yards of track under my feet. The tape meant finality - extinction perhaps. I felt at that moment that it was my chance to do one thing supremely well. I drove on, impelled by a combination of fear and pride.” (6)

Guttmann contends that these two moments in the life of the same man illustrate the shift from traditional play to modern sports. In using the expression “tradional play,” I am raising the thesis of Johan Huizinga, for whom play is an essential characteristic of man: In Homo Ludens, Huizinga seeks to persuade us that the gift of play defines the essence of human beings better than either thought or action. Sapiens? Are we really so reasonable? Faber? How does that distinguish us from many animals? “The existence of play affirms, permanently, and in the most exalted sense, the supra-logical character of our place in the cosmos. Animals can play: they are already thus more than mechanisms. We play, and we are conscious of playing: we are therefore more than rational beings, because play is illogical.”

Let us note in passing that to define human beings by play rather than reason is to make the definition of man more inclusive – broader. Peoples and individuals we have – at least partially – excluded from humanity, by attributing to them some kind of pre-logical mentality, are reintegrated into it by virtue of this new definition. So what is play for Huizinga? In complete opposition to the traditional conception of play, which the ancient writers saw only as a degraded form of ritual or sacred practices, and in contrast to activities necessitated by the demands of life, Huizinga held that culture is the product of play, that play stimulates ingenuity and the capacity of human beings to conceive rules to frame their existence, to delineate a territory where base greed and the will for domination seek to express themselves without destroying a precarious social order.

He defines play as an ''an activity which proceeds within certain limits of space and time, in a visible order, according to rules freely accepted, and outside the sphere of necessity or material utility. The play-mood is one of rapture and enthousiasm, and is sacred or festive in accordance with the occasion. A feeling of exaltation and tension accompanies the action, mirth and relaxation follow.” (7) When Huizinga notices then that sport is progressively losing its ludic dimension, it is not only a dehumanization of sport he diagnoses, it is dehumanization in the absolute sense of the term.

But getting back to Bannister. By all accounts, he was an amateur in the best sense of the word. He only trained 30 minutes a day; he had not yet left the sphere of play when he ran the mile in less than four minutes. In so doing, he resembled Abebe Bikila, the barefoot runner who created a sensation at the Games in Rome in 1960, more than he resembled the manufactured and doped athletes of today.

Among the other pieces of evidence that can be adduced in support of the notion that sport is defined by science is the strict connection that can be seen between the notion of sport in a particular epoch and the current dominant metaphors of science. The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were characterised by the body seen as machine, a simple machine such as a lever. In the nineteenth century, the idea of the energetic body appeared, with the steam engine as its model. The twentieth century is that of the programmed body, and the computer as the model machine.

It would be very surprising if sport today could be affected by science and not by other characteristics of modernity such as specialization and bureaucratization. Allen Guttmann, among others, understood this well; this is why his description of modern sport seems so apt. He sees in it seven major characteristics: secularism, equality, specialization, rationalization, bureaucracy, quantification, and the quest for records.

Characteristics of Modern Sport

Secularism

Modern sport is not religious. This seems clear, even if some writers believe that it displays characteristics of religious rites or rituals.

Equality

This is, obviously, an issue of equality of opportunity. It is out of respect for this principle that different tests were established for men and women and for youth of specific age ranges.

Specialization

The steps in the training of an athlete resemble the stages in the manufacture of a race car.

Bureaucratization

The International Olympic Committee is the equivalent of the United Nations. The corporations that own professional sports teams are bloated bureaucracies; so too are players’ associations.

Quantification

Statistics have long since replaced poetry as the language of sport. And every day we invent new ones.

Record

This is where all the other characteristics converge.

We think it is important to complete this list by adding three other characteristics:

Modern sports, professional or Olympic, are a hunt preserved for those 15 to 35 years of age.

Heightened Ecological Footprint

Evidence of this reality was adduced above in relation to Cardiff.

Globalization

With the exception, often noted, of baseball and American football, modern sports have a tendency to spread throughout the entire world and to replace traditional sports, where they still exist.

Institutions in decline often enjoy a triumphant period just before their death. Such was the case of Gothic art. The builders of the Beauvais Cathedral in the early thirteenth century went beyond excess. The nave had barely been completed when the first repairs were required to support it. Centuries of errors and repairs followed, and new excesses followed those repairs until, in the sixteenth century, a 150-metre bell tower was erected. It promptly collapsed.

The prodigious efforts that have been made during the 2010 Vancouver Olympic Games to repair the slopes after the rain; the fresh water that had to be diverted toward Beijing on the occasion of the Summer Games of 2008 – might these excesses announce the end of this institution? At the same time, we must consider the evidence that interest in records will inevitably fade away sooner or later. When we will have used every trick – licit or illicit – to save a fraction of a second, we must clearly face the fact that instead of a record to be surpassed there will soon be an insurmountable wall.

We might also expect that their popularity would diminish little by little. This would inevitably be the case if all those gains in sustainable development showed some minimum of coherence. What good is it, though, to reduce the engine size of automobiles if, at the same time, we multiply the number of large indoor sports centres we can’t get to except by long car trips?

This is the most obvious reason to rethink sports. It is not the most profound, nor, doubtless, is it the most decisive. Let us remember Bannister. As a child, at play, he enjoyed a symbiotic relationship with nature; what he recalls is a veritable cosmic ecstasy. Later, at the moment he broke the record for the four-minute mile, he was alone with himself. It was his spirit that would have taken control. The modern scientist analyzes nature but has also become a stranger to it. It is this vision of the world, centred on triumphalist science, that is in decline.

Another vision of the world is beginning to take shape, centred on what might be called “restorative science,” based at one and the same time on the need to repair the errors made by triumphalist science and on a newly recovered respect for nature. Bio-mimicry and permaculture are good examples of restorative science. Rather than simply jumping on the bandwagon of the most recent discovery and seeing in it an easy way of transforming the world, without considering possible side-effects, we wish to take the time to study a phenomenon in depth, to consider it in its context before thinking about extracting applications from it. These applications should also be imitations of nature more often than transformations of it.

This dream will however not be realized unless we once again draw close to nature, and that presupposes we will protect and rehabilitate it. Sustainable sport is a way to get closer to this goal; the best way to design it is to re-envision the ten characteristics of modern sport.

Characteristics of Sustainable Sport

Secularism ... Sacred

Some sports, like canoe-camping, trekking, and mountain-climbing, awaken the sense of the sacred even in those among our contemporaries most separate from it because of their lifestyles. There is nothing stopping us from doing such activities more often. Are pilgrimages sport? What does it matter? They are beneficial exercise that put their followers on the path of the sacred. One might say the same thing of yoga.

Equality ... Belonging

In the organization of play in a community, we have a choice between two criteria: belonging or equality. We can choose to form a team either with people from the neighbourhood, regardless of their age and skill, or with players of equal skill. In the latter, belonging is less important. In the former, belonging is the most important issue. Where there are outdoor rinks, the teams that are formed usually include girls and boys of all ages. So no one is excluded, not even the small child who can barely stand up on skates. These are generally times of great joy.

Specialization ... Harmonization

To restrict oneself to one sport in order to have a better change to succeed at it is to become a slave to that sport – it becomes more like a job. As a matter of course, we are more likely to become harmonious beings if we enjoy many sports rather than focussing only on one.

Rationalization ... Spontaneity

There is a great deal that is illogical about play. Why reduce that aspect of our lives, which are already excessively rational?

Bureaucratization ... Spirit of Initiative

In most villages in Quebec, up to the end of the 1950s, young people had to organize teams themselves and raise the money they needed to take on the teams of neighbouring villages. Some years we didn’t succeed in creating enough teams to form a league, and we had to show more initiative the following year. Between the bureaucracies of today and this laissez-faire attitude of yesteryear, isn’t there some kind of middle ground?

Quantification ... Quality and Art

We have only to look at one of Hendrick Avercamp’s paintings of winter sports in Holland or a Greek sculpture like the Discobolus, or to read a poem of Pindar’s to see that we would all win by practicing sports that can be a source of inspiration for painters, sculptors, and poets.

Record ... Emulation

Measuring oneself against another is part of play. But during village fairs, when we play tug-of-war, does anyone care about breaking a record? Do we enjoy it less because we don’t? The reward for the effort expended is less important than its very nature. So a distinction between emulation and competition is called for. Founded on admiration, emulation is a generous feeling, whereas competition is more attached to rivalry. “Rivalry and emulation do not seek to achieve the same goals,” Littre explains. “Emulation’s goal is to surpass in merit, virtue, etc.; rivalry’s goal is to dispute possession of some product, of power, riches, a woman, etc.”

Ageism ... Sport For All Ages

Walking, exercising at home, gardening, and bicycling are the most popular physical activities in Canada. They are both sustaining and sustainable sports: They can be done by people of any age, and they help sustain the life of the planet. The same is true of swimming and cross-country skiing.

Ecological Footprint ... Local Resilience

Because we are more likely to meet him or her in the street, or talk to or touch him or her, if we give children the opportunity, they will identify more closely with a local star than with some far-off sports celebrity. This local focus enriches the community, and that has positive spinoff effects on the physical environment.

Globalization ... Acting Locally

Professional sports and the modern Olympics are going global because they increasingly belong to the world of work and business. If we bring them back toward play, they will return to the place that common sense says is theirs: the neighbourhood. Heads of state and thinkers must meet in Beijing this time and at another time in Geneva. We must be able to fly from everywhere in the world to come to the aid of a devastated country. These things are and will remain necessary. On the other hand, travelling more, and at a faster and faster pace, to engage in professional sports games, more and more of them every year – these extremes are not justifiable as if they were the sine qua non of widespread and sustainable practice of sport and physical activity in general.

This is manifestly not the case. In Canada, the number of adults involved in sport is in decline. It dropped sharply between 1992 and 2005, from 45 percent to 28 percent. (5) During this same period, opportunities to watch sports on television multiplied. As for children, the picture isn’t much brighter.

Considering the sedentary life that more and more people lead, hours spent in front of a cathode screen at home, at work, or at school, considering the increase in the amount of leisure time available, physical activity and sport in general should be taking on more and more importance in our lives.

It is to be feared that the principal effect of modern sport, which is also a spectacle, a show, is nothing more than a way of exposing people to publicity and making them ever more passive consumers. One thing is absolutely certain: They don’t participate in the sports that they watch. Walking, gardening, doing exercise at home, swimming, bicycling, and jogging, in that order, are the most common sports and physical activities enjoyed in Canada.

These are all sustainable sports, and if the media accorded them as much importance as sports spectacles, isn’t it reasonable to think that they would become more popular? If, for example, each evening on the news, we saw an interview with a pilgrim to Compostela or with someone who walked the Appalachian Trail, surely such extended hikes across the earth and under the sky would attract more enthusiasts. In the vision of sustainable sport, a first principle is that it is the charms and proximity of a vibrant street or beautiful scenery that impels people to move. Beauty and life attract us the way the nesting site attracts migratory birds. It is this appeal that is sustaining and sustainable, whereas the effort of will involved in the pursuit of an external end, even if it is health, is quickly abandoned. The construction of a big, indoor sports centre makes people think that it will make them more active. But they will abandon it as quickly as the gym equipment they have just installed in their basement. But beautify the street that leads to a park where other walkers give them a bit of attention, and you will see them move toward this life. These gradual beginnings of life, we have to remember, don’t lend themselves to planning. The living landscape doesn’t create a vibrant society. They fertilize one another, and are born and reborn at the same time.

Notes

1. Allen Guttmann, Du rituel au record, la nature des sports modernes, Paris: L'Harmattan, 2006, p. 125.

2. Hans Lenk, Leistungs sport: Ideologie oder Mythos?, op. cit., p.144.

3. Jacques Ullman, De la gymnastique aux sports modernes, 2nd ed., Paris: Vrin, 1971, p.336.

4. Ludwig Klages, , Les principes de la caractérologie, Paris: Delachaux et Niestley, 1950, p. 122.

5-Allen Guttmann, Du rituel au record, la nature des sports modernes, Paris, L'Harmattan, 2006, p 18.

6. Allen Guttmann, op. cit., p.115.

7. Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens - Essai sur la fonction sociale du jeu, Paris: Gallimard, 1951, p.35.

The editor of L'Encyclopédie de L'Agora and well known newspaper chronicler and philosopher, analyses actuality through the looking glass of Belonging.

The editor of L'Encyclopédie de L'Agora and well known newspaper chronicler and philosopher, analyses actuality through the looking glass of Belonging.